A World That Someone Else Owns

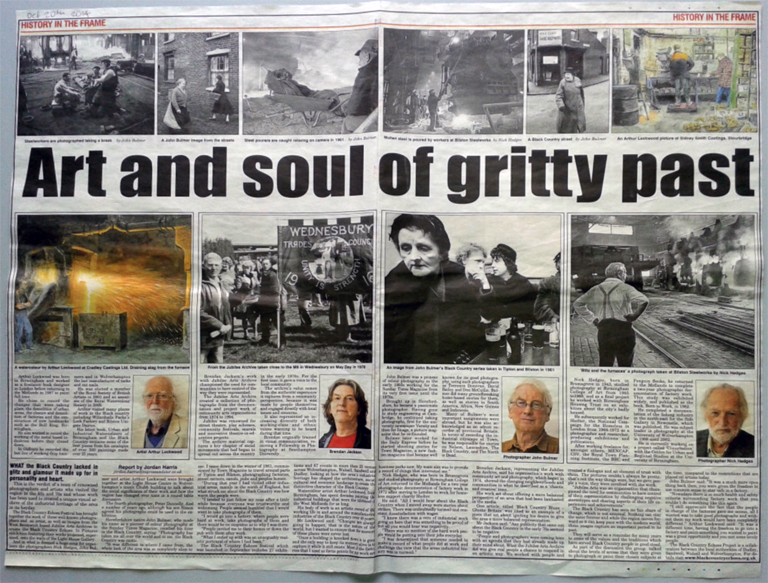

Essay commissioned for the Black County Echoes Festival catalogue, a year long celebration of local Post-War manufacturing history, with over a million visitors attending 27 exhibitions and 87 events in 25 Black Country locations.

(Image: Chance's Glass Factory, 1960's from Jubilee Arts Archive)

The Black Country has always drawn migrants to it, from its very beginnings: former agricultural workers from the shire counties on all sides, displaced by mechanisation and drawn to the new kinds of work offered by the factories of the Industrial Revolution; French Huguenot refugees, escaping religious persecution, who brought their enamelling enterprise here; Irish labourers who came to dig the canals and later work the railways; glass workers from the Low Counties, whose industry had collapsed in the European revolutions of 1830 and whose skills were in demand by English entrepreneurs. Later, in the post-war world of 1945, there is the more contemporary migration story of people from the Commonwealth countries of the British Empire, whose labour was required – and duly solicited – to rebuild the country.

I was born in the Black Country. I know it well enough. My forebears travelled from North Wales and Ireland to work here, in the mining industry (on my Father’s side) and in nursing (on my Mother’s side). It so happens I entered the world on the same maternity ward at Hallam Hospital as Robert Plant, though some years later. I can still pick out the bit of tarmac purportedly laid down by the future rock god on West Bromwich high street, when he worked for a time as a labourer for the corporation, well before he found the stairway to heaven. This shrine was once solemnly pointed out to me by an old fellow from the works department of the council. There are no known photographs that record this historical moment, merely a memory, an anecdote, a story, passed on from one person to another. While, compared with our past output, we may not create much ‘stuff’ in the Black Country anymore, we have stories aplenty, a rich vein to be mined by artists, writers and performers. This inside view of the area has received little attention and the views of the outsider have traditionally been pejorative. It’s a place most people drive past on the motorway. When the area has received national media attention, it has been overwhelmingly negative – a trend that may have started when Queen Victoria visited Wolverhampton one dismal November day in 1866. Following the death of her husband and a period of mourning, it was her first appearance in public for five years. She purportedly asked for the blinds of her railway carriage to be drawn to hide the view of the hideous industrial landscape, this dreadful black country her couriers had brought her to. Arriving at the station she was greeted by a 40ft arch made of coal, through which her carriage passed. This may have compounded her poor impression of this particular part of her kingdom. Balmoral it was not.

These unfavourable views persisted and persisted. In the 1930s, J.B Priestley wrote: ‘Industry has ravaged it, drunken storm troopers have passed this way; there are signs of atrocities everywhere, the earth has been left gaping and bleeding; and what were once bright fields have been rummaged and raped into these dreadful patches of waste ground’. This was the environment where new migrants arrived in the middle of the 20th century – as post-war settlements helped create a world that was increasingly interconnected, where economic migration was to become the norm, a movement of both people and capital. To the Black Country came the Poles dispossessed of their homelands by the fall of the Iron Curtain across Europe, the workers from the West Indies encouraged to pack their suitcase and help fill labour shortages in the ‘Mother Country’, Pakistanis and Indians to work in the steel and textile industries. Until the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962, all citizens of the Commonwealth could enter and stay in the UK without restriction. By 1960, nearly 40 per cent of all junior doctors in the NHS were recruited from the Indian subcontinent – in 1963 alone some 18,000 were recruited, in a campaign led enthusiastically by none other than the Wolverhampton MP Enoch Powell.

As an artist motivated to engage with the lessons of history, I am happy to be spending time investigating an archive of unique photographic material that documents the people and places of this much-maligned area. The Jubilee Arts Archive in Sandwell contains more than 20,000 images from the years 1974–94, documentation of community projects undertaken by those artist activists. Here we find a portrait that reflects not just the Black Country but also the changing demographics of British society. Here we find evidence of the growing diversity of the formerly colourless Black Country.

In 1984, in a Britain preoccupied by a 12-month long national miner’s strike, the Sunday Times sent a journalist to Sandwell to write a piece called ‘Black Country Blues – Ghetto Britain’. The journalist described his experience of Sandwell as ‘probably the most depressing story I have ever worked on in my career’. At the time, Jubilee were working with a group of young break dancers to create a performance, a kind of break-dance ballet representing a day in their life. They called themselves the Smethwick Spades AKA The Crazy Spades. They were predominantly African-Caribbean, with a smattering of White and Asian members. They looked at this article, with the words and images from the outside that portrayed their town and life as a place of poverty and helplessness, and they didn’t see things in quite the same way. Though this was no longer the same centre of industrial production, they saw it as a place enriched by the experience of people from all over the world, which their parents, brothers and sisters had contributed to. Their discussion was animated and they mused on the origins of the naming of this place, as have so many others. Their rationale was: ‘Well, it’s just called that now because of all the black people who have lived here.’

They were fascinated to find out about a local factory notable for producing the glazing for both the Houses of Parliament and the famous 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations at Crystal Palace. Once a hotbed of innovation, Chance Brothers ceased producing flat glass in 1976 and the remainder of the works closed in 1981. Their buildings were in a ruinous state – some can be still seen standing by the canalside today, at Spon Lane junction, along the Wolverhampton to Birmingham railway line. (Sandwell was soon to be noted for having the second highest proportion of derelict land in the country, a legacy of this industrial past.) The young break dancers spoke to a Jamaican man who used to work at Chance’s in the 60s; he told them how it was a good place for black people to work. Old Mr Chance looked after his workers, he told them.

There were other places with a word-of-mouth reputation for welcoming the new migrants and their skills and enthusiasm. In Bilston, Beverley Harvey recalls her first job after leaving school, at Bradleys – a factory originally founded in 1882, which finally shut up shop in 2005.

“I didn’t have any experience, leaving school at 16 in the 1970s, and they put me on the hand press straightaway. I was at the first aid every day until I worked out how to avoid the pieces that sprang back. Bradleys made ladders, wheelbarrows, ironing boards. They even had a black foreman back then. The first generation of black people who worked there encouraged us to look ahead, to better our circumstances, not to stay on the factory floor. I remember it as a big happy family. We used to warm up our coco bread and fish on the furnaces. People would want to try it and see what Caribbean food tasted like. There was a white woman, Gladys – she was Irish actually – who told us all about strikes and our rights.”

Black and Asian workers were prone to exploitation and poor working conditions and discrimination. American civil rights activist Malcom X visited Smethwick in 1965, where white householders were lobbying the council to buy up houses to prevent black or Asian families moving in. Avtar Singh Johal, an activist with the Indian Workers' Association, went for a drink with him in a local pub – one of a few which did not operate a colour bar. It was the concentration of foundries locally that attracted the migrant workers; Johal first came in 1958, to work as a moulder’s mate at Shotton Brothers in Oldbury. He soon found out he had half the pay of the exclusively white moulders. It was tough work – this was a time when the average life expectancy of a man in the moulding plant was 34. Later he worked at Midland Motor Cylinders in Smethwick, where he successfully challenged the rule of separate lavatories for Asians and Europeans. It was these migrant workers who were often at the forefront of campaigns – in 1982 Sikh women organised strikes over low pay and for union recognition at Supreme Quiltings and Raindi Textiles in Smethwick and were visited on the picket line by the then Labour leader, Michael Foot. It was the migrants, both men and women, who filled the Victorian age factories, as the white working class increasingly took up the expanded educational opportunities offered in the 1960s.

These materials and stories live on in the archives, forming part of the fabric of the Black Country. Jubilee Arts was a group that championed the need for communities to have control of their representation, challenging negative stereotypes, sharing aspects of their life experiences and common values. These images will outlast our own memory of them, and will be found again and seen differently in another 100 years. The projects of the past can be windows to the future; through the involvement and engagement of local people we can continue to be proud of our diversity, to tell the unknown stories and celebrate our achievements. But let us not over-romanticise those good old days. With the fragmentation of work and increasing use of zero hours contracts, an increasing separateness and lack of control, it seems we are in transition to a third world economy (as the term was formerly understood). We are more introspective, less sure of ourselves. Now, to all intents and purposes it is a world that someone else owns. But what we retain is our imagination and that surely allows for hope.

Brendan Jackson, September 2014

References

Derek Bishton and John Reardon, Home Front, Jonathan Cape, 1990

J.B Priestley, An English Journey, Victor Gollancz, 1934

Sujinder Singh Sangha, ‘The Struggle of Punjabi Women for Trade Union recognition’, unpublished paper, Industrial Language Unit, Bilston Community College, 1983

Jane L. Thompson, All right for Some, Hutchinson, 1986

Download pdf of catalogue: BCE-Publication-LOW-RES