Bert Williams

“There is an old saying, the outsider sees most of the game”

Where is to-day’s Bert Williams? In the April 1952 edition of Charles Buchan’s Football Monthly, Bill Murray - then manager of Sunderland - asked this question: ‘Whither are we going?’ Football, he decided was in a parlous state. He thought there were too many reforms and rule changes - the latest being the suggestion that a full back should not be allowed to pass the ball back to the goal keeper. He thought there was not enough football for the fun of it, with attempts to turn football into a science with robots - which he believed to believed to be the product of over-coaching. And to top it all there was the application of inappropriate business methods to the running of a club.

He wrote: ‘One bright sunny afternoon someone will awaken and discover that football is a game and go into sackcloth and ashes over the loss of reams of paper, gallons of ink and years in hours which have been utterly wasted on the bilge written about the sport.’

One of the revered players in those post-war years in England was Bert Williams, who kept goal for Wolverhampton Wanderers. He was born on 31st January, 1920, in Bradley, Bilston. “It wasn’t an affluent area, but people knew the basics of loyalty and good living. It was a good background to be brought up in. We used to go down bird nesting at the Rocket Pool, Pothouse Bridge. There used to be a brook running along, and watercress used to grow in there and people used to gather it. One thing about the Rocket Pool, one of my friends got drowned swimming in that pool. Strangely enough we used to swim in the canals. There was a large factory by the canal side and it used to eject surplus hot water. It was lovely swimming in all that hot water.”

When Bert finished school at noon, after fetching some groceries for his Mom, he would take his Dad’s dinner up to the works - bread dripping sandwiches, pork or beef. The factory was about a mile away, he would run all the way there and back. After Saturday choir practice, whenever possible he would go to study his favourite, Harry Hibbs, who kept goal for Birmingham City.

Other times he went to games with his Father, who was a Baggies supporter and who had also played in goal - though Dad didn't progress far, as he wore glasses. “I had tuppence pocket money then. I’d spend one penny at the fruit shop on the bad apples, oranges, bananas. The other went on sweets.” Bert worried he would never be tall enough to be a goalie. At five feet tall, he used to get his four brothers to swing on his legs as he hung from a beam, in the hope of increasing his height. When he first played for Walsall as an amateur, he was only 5 feet four inches. He eventually grew another 6 inches.

He left school at 14 and went to work at the Thompson Brothers engineering factory. He played for the works team there. Bert recalled: “I’d been playing for the pick of Bilston schoolboys and one night the manager of Walsall came over to see me and asked if I would sign for Walsall. I signed. This was my dream, I didn’t want to do anything else. It was Friday. He said, ‘On Monday we’ve got a match at the Hawthorns’ and that was my first match, playing for Walsall reserves against the Albion whom I’d always supported. When I turned up at the ground, the trainer said, ‘What do you want, son, an autograph?’ I said, ‘No, I’m playing.’ My Father gave me his cap. He said, ‘The sun will be in your eyes, wear this.’ He told me to show confidence. ‘Now if they have a penalty throw the cap in the corner of the net as if you hadn’t a care in the world.’ Of course, they had a penalty. So I did that, but the forward kicked it so hard it would of killed me if it hit me. It whistled into the back of the net. We lost that game by one-nil, and I thought, Well that didn’t work.”

When Walsall decided to sign him as a professional, at the age of 17, they said to him ‘We’ll give you a pound in the summer and one pound and ten shillings in the winter when you play a match.’ The wage he got at the factory was eleven shillings a week, so it was a good uplift. He played 25 games for the club before the outbreak of the Second World War. During that conflict he served in the Royal Air Force as a Physical Training instructor. He signed for Wolves in September 1945 for a £3500 fee, making his debut against Chelsea.

He made 420 League and cup appearances for them, winning the FA Cup medal in 1949 and a League Championship medal in 1954. He won his first international cap for England against France in 1949, and played in the 1950 World Cup Finals in Brazil, where England were surprisingly beaten 1-0 by the USA.

Only the year before, Bert produced one of the best performances of his career in a 2-0 England victory over the world champions Italy at White Hart Lane in front of 70,000 people. That afternoon in 1949 the Italian players nicknamed him ‘Il Gattone’ - The Cat - for his remarkable saves. Of that legendary day all he said was, “Football is fifty per cent ability and fifty per cent luck, being in the right place at the right time. Some days everything went right and that was one of those days.”

Bert added to his reputation three days just after the Italy game when at Highbury he saved a penalty from Arsenal's Walley Barnes, who had never before missed from the spot. Arsenal gave Bert the unusual accolade of being the only non Arsenal player to be featured on the cover of a their Highbury match programme, putting a photograph of the save on the cover

Another memorable occasion was one of a series of international friendlies held in mid-week, precursors of the European Cup competitions, which were made possible by the newly installed floodlights - ‘a wonderland’ said the press. The Hungarian team, Honvéd, came to play at Molineux in December 1955, in front of a crowd of 55,000. English football was in a state of deep embarrassment after two crushing defeats suffered by the national team at the hands of Hungary, 6-3 in 1953 and 7-1 a year later. Five players from the national team were in the Honvéd side this night. The Times, reporting on the match, said: ‘Wolverhampton did British football proud under the night sky. To recover two goals lost in the opening 14 minutes to such opposition, and then to snatch the final victory, was a performance in skill, team spirit and stamina that needed no batteries and pylons of glittering arc lamps to illuminate it.’ Even the Daily Mail was moved to declare Wolves to be ‘Champions of the World Now’.

These were the days when South Africa, Glasgow Celtic, Racing Club of Buenos Aires, First Vienna, Maccabi of Tel Aviv and Moscow Spartak all came to play at Molineux, and were soundly beaten – with the exception of Vienna, who held Wolves to 0-0. Before the match with Moscow Spartak, John Thompson, one of the writers for Football Monthly noted a local fan give a clenched fist salute of Communism then sing God Save the Queen. He wrote, ‘I wondered if any other land but this blessed realm of ours could produce a such a sweet contradiction...’

Williams said he used to spend a lot of his training time not goal-keeping at all, but taking up imaginary positions “to stop imaginary shots from various angles – shadow goal-keeping like shadow-boxing.” He retired from the beautiful game at the end of the 1956-57 season. His last competitive match at Molineux was a 5-2 victory over West Bromwich Albion.

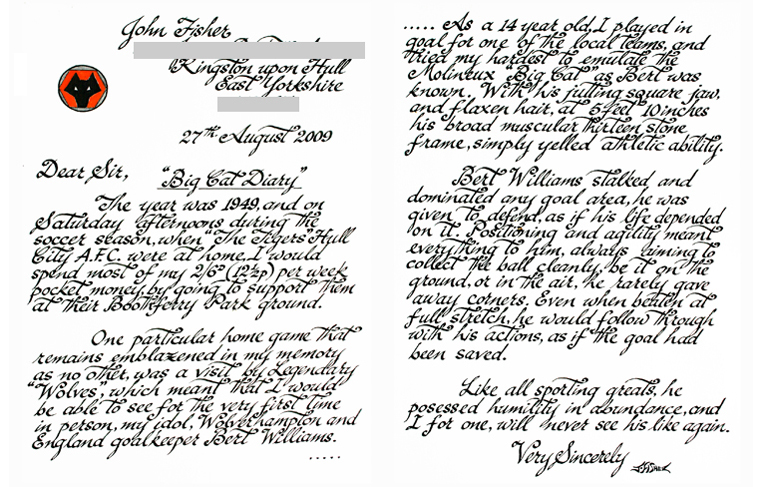

A fan from Hull, John Fisher - who as a 14 year old played in goal for a local team - saw Williams play a friendly at Boothferry Park in 1949. He never forgot the seeing this match. “I was brought up on old school goalkeepers and I used to see Bert Williams on the Gaumont news films and he was different. This fellow was way before his time. He’d be taking control of the whole area, instructing his full backs, marking out a line with his heel so he could always see where he was positioned. I was in the dug-out at Boothferry, in the thrupenny end. I was hoping he’d be defending this goalmouth in the first half, before it became too crowded, and he was, just a few feet away. It’s stayed with me like a photographic memory.” Later, in 2009, John wrote: “With his jutting square jaw, and flaxen hair, at 5 feet 10 inches his broad muscular thirteen stone frame, simply yelled athletic ability. Bert Williams stalked and dominated any goal area, he was given to defend, as if his life depended on it. Positioning and agility meant everything to him, always aiming to collect the ball cleanly, be it on the ground or in the air, he rarely gave away corners. Even when beaten at full stretch, he would follow through with his actions, as if the goal had been saved. Like all sporting greats, he possessed humility in abundance, and I for one, will never see his like again.”

‘There is an old saying, the outsider sees most of the game’ was an installation I created with images and texts for The Combermere Arms, Wolverhampton for a local arts festival. This pub has kept a lot of framed material in relation to the local football team, Wolverhampton Wanderers, and this form of memorabilia was reworked and remixed to create a homage to the legendary sportsman. The title came from an enigmatic answer Bert gave to a news reporter at the height of his career, when asked his opinion on what are the key skills of a goalkeeper. I had the pleasure of meeting with Bert and interviewing him for the project.

A new 14.6 million Leisure Centre named in honour of Bert Williams opened in Bilston in 2012. Bert passed away on 19th January 2014. When will we see his like again?