Highways and Byways

A single walk in straight line

The sea is calm enough, a little bit of breeze but not the kind of blaster to blow the cod inshore. He’s been here since 6.30am and now it’s early afternoon. I’ve had a few nibbles, nothing much, he says, but I really don’t mind, I just love being out here. He carefully skewers lugworm onto a hook. He also has some squid as bait for the cod, but he might save that for another day. In the warmer months, this beach is a popular site for mackerel, when they can come inshore in large numbers. Some old second world war sea concrete defences, known as the Dragon’s Teeth, tumble down into the sea, and it’s here they say is the best mark for the fishing. The fish can be caught at close range as the beach shelves steeply. What can you catch here? In the summer, Bass and Gurnard, Bream, Dogfish, Scad, Trigger Fish and Flatties. Mackerel of course. Now, in winter, Cod and Codling, Whiting, Plaice and Rockling. I don’t know half these names they tell me, so I nod and smile. Well, good luck, I say and carry on my way. In the distance it’s clear and sharp enough to make out the lighthouse at the end of the Isle of Portland.

A Circular Walk around Eggardun Hill

At the end of the old roman road from Dorchester, the ‘Highway of the West’, at the spur of a curving ridge rises the Iron Age hill fort of Eggardun. It may be lesser known or appreciated than triple ramparted Mai Dun, but the views from here are far superior, of countryside that has barely changed in my lifetime, or perhaps even in the last three hundred years. The sweep of the coast towards Golden Cap and Devon beyond, the dazzle of the sea, a glimpse of Pilsdon Pen, in between the soft hills and downs, woods and valleys, scattered farm buildings, strip lynchets revealed by the angle of the sun. Now only inhabited by rabbits and sheep, these slopes and ditches were constructed of huge mounds of chalk, no doubt a gleaming white beacon when first raised up by the metal users. The bareness of the grass now testifies to ‘a long friendship with rough winds’, as one walker described these heights in the 1930’s, striding past with her puppy dogs, Bill and Mr Bundy, heading for Burton Bradstock and the Chesil Bank. Some years later, one farmer-writer from these parts gazed at a fossil in his hand (he called them books of stone), thrown up from ploughed chalk on the downland. He looked out over the landscape, at ‘nature’s vast, relentless roll’, reflecting on the rise and fall of empires, the clash of nations, massacres and crimes, past glories of philosophy and art. He told himself, ‘Here, order does not break.’ Today the wind relentless as ever, I ponder the wonders of the modern age; the flushing toilet, running water, a mirror, a cooking fire.

A semi-circular walk from Overcombe to Nothe Fort

I am not staying in the old seaport and pleasure resort, which was once called ‘The English Naples’. I never have, though I know several folk who booked a bed and breakfast or caravan over the years, enjoying the extended frontage – the bay is nearly five miles across. Such visitors were was once noteworthy, articles in the Dorset Daily Echo reporting the arrival of 500 families from the Black Country by train in just one weekend, determined to enjoy their holiday here in Weymouth, surely cementing its reputation as a premier destination with ‘wonderful sands, a good water supply and a splendid climate’. Had they a Black Country flag back then, they would have been as popular a purchase as those paper ones of the Union Jack, of Saint Andrew and the Welsh Dragon, along with miscellaneous emblems of France, Italy and Spain that adorned a thousand sandcastles. (I don’t remember there being an Irish flag available).

Though locals disdainfully called these holidaymakers ‘grockles’, a visitor in 1804 was far less charitable of the locale itself. He intended to visit his brother who was with the Royal Squadron in the bay. On arrival, he paid the modern equivalent of £58 to a local boatman who dropped him at the first royal barge in the bay they came across, which is then stranded in an impenetrable sea mist and while waiting for dawn runs foul of a cable. Finally he is rescued by the crew of a cutter at anchor who finally take him back to shore. Then he spends his first night’s lodging being tormented by all manner of vermin. He does eventually meet up with his brother, but during his stay he is not impressed by the countryside hereabouts, complaining that he can find no shade from the scorching sun. He thought it a bare and barren place, and the cost of staying here horrendous, prices inflated due to the King’s visit. When he left Weymouth after a week, he was forced to travel slowly as his horse ‘seemed literally starved, his ribs starting through his skin’, although he had paid an outrageous sum of one guinea for his keep.

Boating in Weymouth is recommended, as one guide from the 1930’s puts it: ‘the bay being free of dangerous currents and promiscuous rocks’. No mention of mist. I took my first cross-channel from here, for 48 hours in France, in storm tossed seas on the return. I have a strong unpleasant memory of sliding across the deck. There is a small memorial here now to the U.S. Forces who left from here to land at Omaha Beach, with a photograph of some of those soldiers marching down the Esplanade. Over half a million of them passed this way (those called 'The Greatest Generation', probably correctly so if we look to current models). The wind whips up the sand of the beach and a few people run with their dogs by the shoreline (please note, dogs banned from the beach between April and October). Here on a Saturday night in Spring 1946 a young woman was carried off these sands on the shoulders of a British soldier. She was hopelessly drunk. An American sailor was also helping carry her. They were stopped by P.C. Otter. The soldier said she was ill and he was going to take her to a room for the night. Neither soldier nor sailor were able to tell P.C. Otter her name or anything about her, so he took her into custody. She was later charged with being drunk and incapable. She was 19 years old, Polish, of no fixed abode; she said her name was Frances Kolosvonksi and that she had only arrived that day from Aldershot to meet her boyfriend who had been posted here. ‘It was the first time in my life that I had a drink and it will be the last time,’ she said. ‘I had an argument with my fiancé.’ The Chairman of the Magistrates Court concluded, ‘I shall think you are very ashamed of yourself, aren’t you?’ If this was a post-modern musical she might burst into song and say ‘You took the words right out of my mouth’. She meekly agreed, ‘Yes, very ashamed’. She was fined 10 shillings, which would barely cover a single room with breakfast at the Crown Hotel opposite the railway station.

A square walk around the walls with a loop south and east

Loosely follow the perimeter of the old Roman town, marked today by Walks originally planted in the 18th century with lime, sycamore and more recently chestnut – these enclose three sides of the town. By more recently we mean over a century ago. A river walk demarcates the fourth side, where one arm of the Frome runs in an artificially constructed channel used for the water meadows that have kept the town from spreading to the north and north east. The river curves here round old sluice gates and the rise upon which is built the prison (itself on the site of a Norman castle) and beyond that the County Council offices. The excavations in this north west corner to build these offices in the 30’s revealed three roman town houses which were then preserved. One fragment of the original wall still remains, near the statue of Thomas Hardy. Crossing the Frome on the eastern side of the town, it is a short walk of two or three miles to the churchyard in Stinsford where his heart is buried beside his first wife.

On the south side, beyond the line of the walks, lay the site of the town market once busy every Wednesday with fat calves, sheep, lamb and pigs. Here there were markets for farm equipment and implements too; sales displays of new combined side delivery rakes and swath turners, a Watson and Harry 30ft elevator, a Bristol caterpillar tractor, mowing machines, plough and cultivator attachments. Now it’s a car park, charges vigorously enforced.

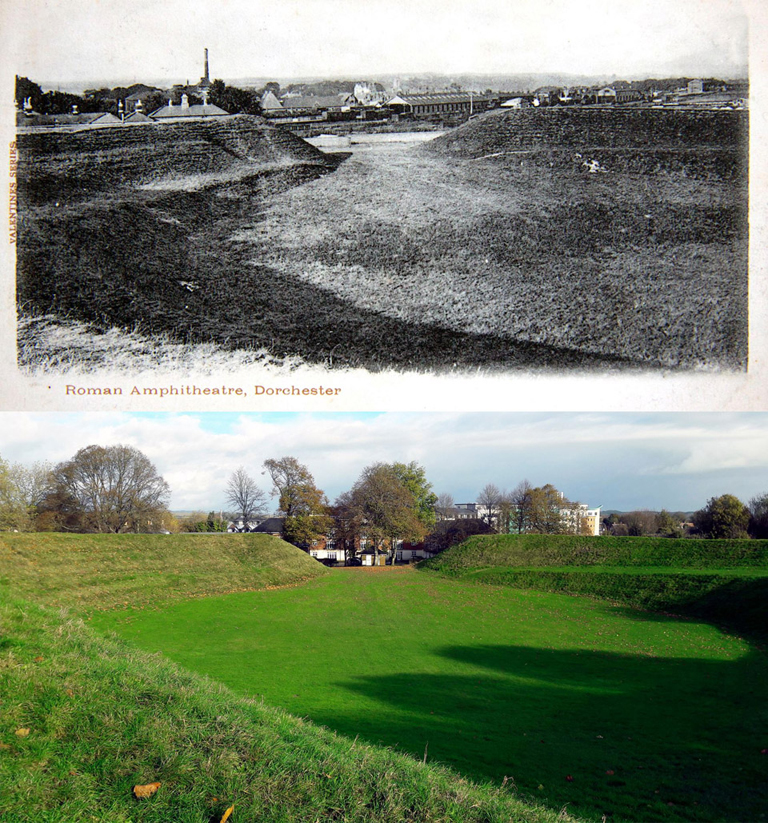

Across the road, next to the Victorian police station, is Maumbury Rings, the Roman amphitheatre. When the railways came, the engineer Mr Brunel wanted to cut right through here, as well as the ancient earthwork at Poundbury on the north west side of the town, thus raising the ire of many an archeologist and historian, who decried this proposal as the work of ‘barbarian perpetrators’ no less. Mr Brunel was reminded that it was the great Sir Christopher Wren who first marveled at the Rings and made them known to the worlds’ antiquarians when, en route to scry Portland stone, he asked for his coach to be stopped, in order to give them a thorough investigation. Brunel twisted his rails so as to avoid the ancient amphitheatre and built a tunnel under Poundbury, ‘as he may frequently have the opportunity of doing mischief, he would always be found most anxious to avoid it.’

A walk from West Chaldon, looking for the ghosts of poets

It is getting cold, they say there is snow in the North. Just before tea it was raining. She fills the fire grate with twigs she has collected, strips of hazel, then adds the shavings of logs and crumpled brown paper that the bread came wrapped in. She lit the fire and contributed some vitriolic love letters she had never sent, as well as scraps of her verse that had no satisfactory conclusion. Finally she tossed in a few logs of ash and yew. Their cottage was somewhat dilapidated but homely enough for the two of them and the room is quick to warm.

Her lover pulls a face and complains that, after one too many doses of veramon, she is prone to roaming about the place looking white and grim. Her mood lifts though when they walk the downs and follow the shady hidden paths. She is cheered at the sight of the local names: Scratchy Bottom, White Nose, Daggers Gate, Five Marys. They sit holding hands on the highest of the ancient barrows, the sea air invigorating their spirits. Then she truly feels as light as a feather. Later, she will listen to the gramophone and manage to scratch out few lines, something secular. She writes, perhaps for herself only:

Is the hawk as tender

To the belly of its prey –

White belly wet with dew –

As I am to you,

In the same way,

My slender?

The President Decides

Captain Hart gave him back the binoculars wearily. ‘Why do we do it, Martin? This space travel, I mean? Always on the go. Always searching. Our insides always tight. Never any rest.’

‘Maybe we’re looking for peace and quiet. Certainly there’s none on Earth,’ said Martin.

‘No, there’s not is there? Captain Hart was thoughtful, the fire damped down. ‘Not since Darwin, eh? Not since everything went by the board, everything we used to believe in, eh? Divine power and all that. And so you think that’s why we’re going out to the stars, eh, Martin? Looking for our lost souls, is that it? Trying to get away from our evil planet to a good one?’

These sentences are from a short story by Ray Bradbury first published in 1949, an author who revelled in the power and imagination of childhood, of magic, rocketry and science. As a teenager I devoured his collections ‘S is for Space’ and ‘R is for Rocket’ on my holidays in Dorset, sitting in the shade of the beach chalet, admiring the bikinis or watching the naval ships anchor in Portland Roads. Little did I know that near this very spot, back in 1946, Mr Hooper of Overcombe, Weymouth, looked out over much the same view and reflected on the power of the Atomic Bomb now in the hands of the Yanks. He had met enough of them over the last few years, 517,816 of their troops and 144,093 vehicles embarking for Normandy from this port alone, most of them decent enough sorts, but the recent public behaviour of their Joint Chiefs of Staff left a lot to be desired. (You will fid a small monument to those troops on the esplanade.)

He was particularly concerned about the effects of uranium. Thirty years of chemistry had led him to believe that May 15th, the date set for the atom bomb experiments in the Pacific Ocean, may be the end of us all. One was to be an airdrop, one underwater. His reasoning was that seawater contains traces of uranium, therefore any atomic explosion over the ocean will ‘almost certainly start off an ever increasing dissolution.’ In addition, he believed it was impossible to test the seabed for uranium; the testing area may therefore be over a large deposit and a catastrophe was surely waiting in the wings. To conduct the tests, 167 inhabitants were moved from Bikini Atoll to Rongerik Atoll, which had no inhabitants due to an inadequate water and food supply and also because of a belief that the island was haunted by the Demon Girls of Ujae. Regardless, the Americans moved 95 warships of all shapes and sizes to the test area, planning to assess their durability to nuclear attack.

As holidaymakers flocked to the coast again to enjoy the sun (though in reality the weather was mixed that summer), Mr Hooper sent letters to the Sunday papers, hoping for some reaction. He wrote: ‘Those of us interested in nuclear physics know of experiments which certainly seemed safe enough in theory, but which nevertheless ended fatally. Let us pray that this much vaster one does not end in disintegration.’ As they say in the local Dorset dialect, it’s a caddle – a puzzling plight, such a confusing situation that a man does not know what to do first. Some might say Mr Hooper was joppetty joppetty – anxious and agitated over the whole cantankerous affair. The world demonstrably did not end on May 15th, nor at the end of June when the first of three tests was actually conducted, no doubt he waited impatiently and wondered whatever would come next.

As the Americans were coming to understand the effects of fallout, in Paris the designer Louis Réard introduced a new two-piece swimsuit, which he called the bikini because ‘like the bomb, the bikini is small and devastating’. While the inevitable appearance of bikinis on the beach front at Overcombe might have led to an increase in his blood pressure, Mr Hooper would I think have been apoplectic had he been aware the US Army Air Force had put forward a plan to the Pentagon the previous September to destroy 66 Soviet cities and were demanding production of 204 atomic bombs to do so. As it was, production of 39 were approved to eliminate 15 first priority targets. Among them, it was estimated 6 each would be required for Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev, five for Lviv, four for Chelyabinsk, three for Tbilisi, two each for Baku and Grozny. While the majority of his cabinet and nuclear scientists supported the idea of international collaboration to control nuclear power and the abandonment of ‘the policy of secrecy’, the President sided with the military establishment and thus the arms race began.