Image: The old town, Tbilisi, 2025.

Morgan Philips Price, a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian sends a postcard to Anna Maria Philips dated 13 March 1917.

“Just a line to say I am well. Most exciting times. I knew this was coming sooner or later but did not think it would come so quickly. Have been running about the Caucasus for last fortnight attending revolutionary meetings. Interviewed Grand Duke Nicholas last week before he left here and telegraphed his statement to M G. Tomorrow I leave for Moscow and then Petrograd. Will keep you informed of my movements. I am not sure what my address will be till I get there... Whole country is wild with joy, waving red flags and singing Marseillaise. It has surpassed my wildest dreams and I can hardly believe it is true. After two-and-a-half years of mental suffering and darkness I at last begin to see light. Long live Great Russia who has shown the world the road to freedom. May Germany and England follow in her steps.”

Postcard of Tiflis, circa 1910.

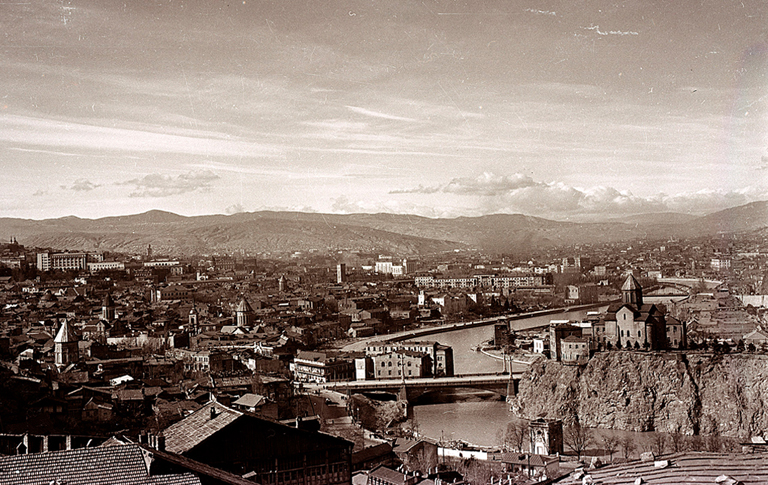

In June 1917, British journalist Robert Scotland Liddell writes in his notebook: “Tiflis in August; white dusty streets – indeed a whiteness and a dustiness covered the whole town: and grey bare hills on all sides. (The snowy peaks could still be seen towards the north.) Tiflis lies in a deep valley, a shallow, muddy river running at the bottom and houses built upon the steep sides. The railway station stands high upon the northern side. From it ones looks down on the town.”

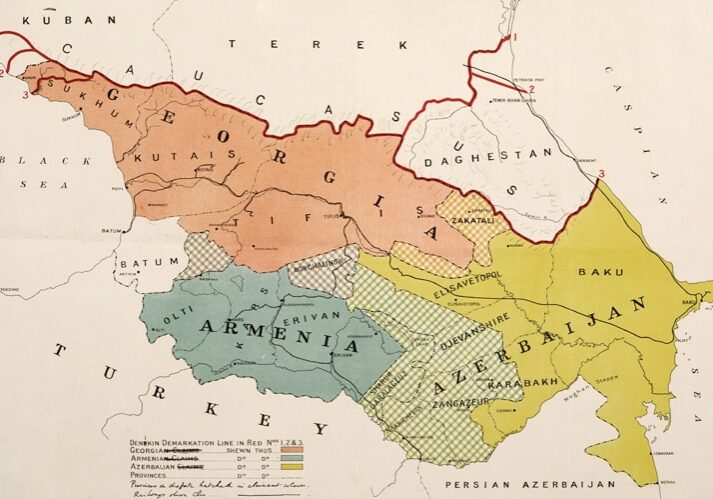

Tbilisi, then called Tiflis, had a British Military Mission in the city for most of the First World War, and a substantial amount of British and Indian troops based at the end of the First World War. Tiflis was then the capital of the newly independent Republic of Georgia. For a time, this city became a refuge for many Russians fleeing the chaos of the Revolution. “One found the strangest people there,” wrote Carl Eric Bechhofer Roberts, another British writer. “Poets and painters from Petrograd and Moscow, philosophers, theosophists, dancers, singers, actors and actresses.”

The city is both European and Oriental. As Agnes Herbert wrote a few years earlier, “We were rubbing shoulders with the remote centuries, and felt the subtle charm of antiquity charged with the vital force of a gripping modernism.”

Headquarters of the British Military Mission, Machabeli Street, during First World War.

Machabeli Street, 2025.

Kate Jackson, a member of the American-Persian Relief Commission, travelled to Georgia in 1918, arriving in the capital city in December. In a 1920 memoir “Around the World to Persia” she writes:

“We arrived at Tiflis at 8 a. m. and found the town all decorated, as it was the first anniversary of the National Guard. We did not like red flags everywhere, but the more moderate natives assured us they were not as socialistic as they seemed. Tiflis is the Capital of Georgia and notwithstanding the fact the country became a part of Russia and was almost Russianised, the natives still retain their language and their love of country. They are crazy now to have a Republic, one of the many this war will produce, and they point with pride to the fact that Georgia is the only part of Russia where Bolshevism was kept out. They have also been Christians since the third or fourth century and one thing that impressed us all, is their great respect for women. As Dr. Judson says, they have a home life, something their Mohammedan neighbours lack. The Committee that took charge of us was composed of very pleasant people, among them a Prince and Princess of old lineage, a general who had been in the Russian army, a very attractive man, a doctor, etc. They gave us three delicious meals, rooms to rest in, and took us sight-seeing, finally bringing us to a train which carried only us, at 11 pm.”

View of the city, circa 1900. Georgian National Archives.

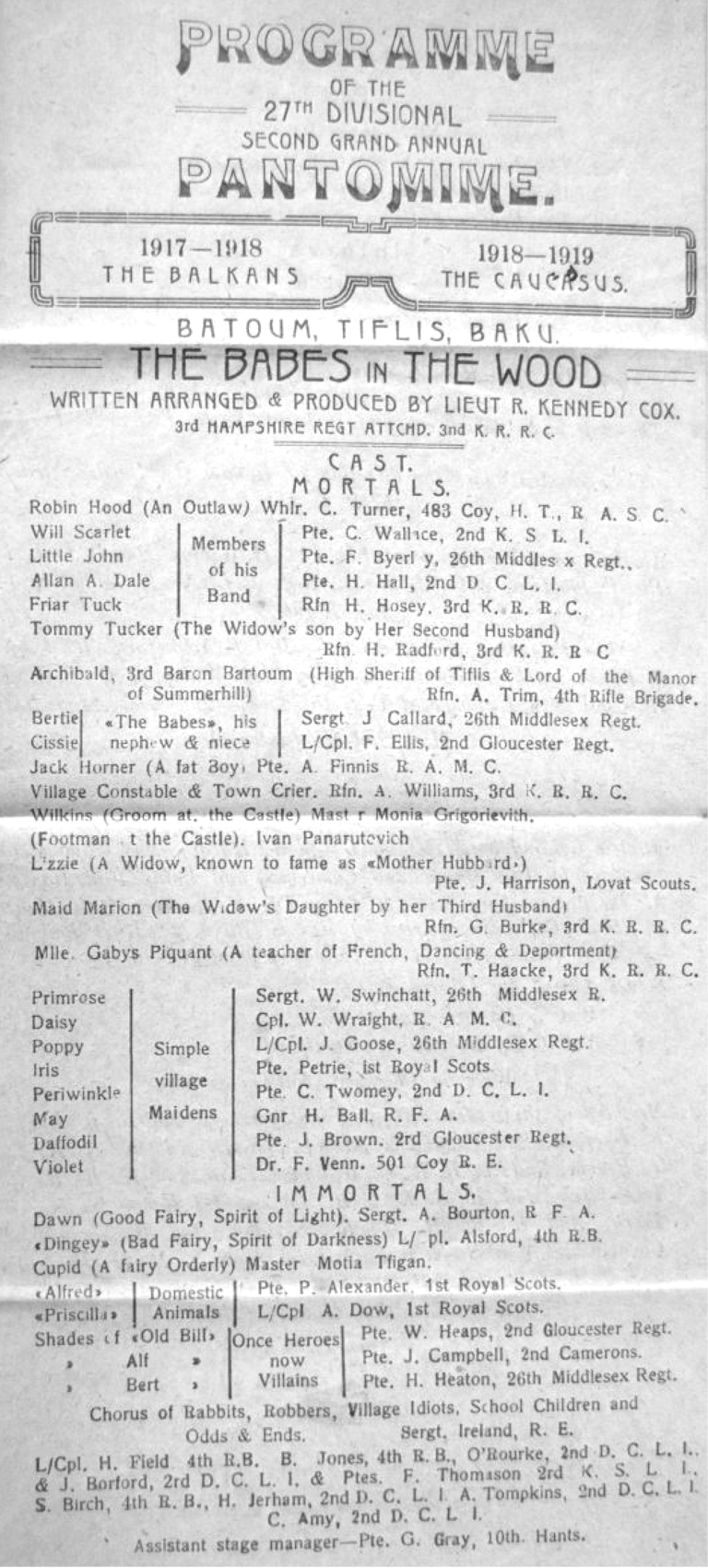

Programme of the pantomime Babes in the Wood, which was performed at Batoum, Tiflis and Baku. Wwritten, arranged and produced by Lieutenant Reginald Kennedy Cox of the 3rd Hampshire Regiment, who in civilian life was a successful playwright.

Oliver Wardrop is sent to Georgia in August 1919 as the first British High Commissioner of Transcaucasus. In his nomination, Lord Curzon wrote: “Mr. Wardrop’s extensive personal experience of Georgia and the Georgians while his long consular service in Russia makes him particularly fitted to carry out such a mission.” Wardrop first visited the Caucasus in the 1880s, learning the language, then publishing a book of his observations and experiences, ‘The Kingdom of Georgia: Notes of travel in a land of women, wine, and song; To which are appended historical, literary, and political sketches, specimens of the national music, and a compendious bibliography’. In it, he noted with optimism: “There is no reason why Georgia should not become as popular a resort as Norway or Switzerland. It is not so far away as people imagine.”

He is accommodated in a fine mansion on Machabeli Street, a few hundred yards from where British forces military intelligence have their headquarters. The house, with art nouveau with neo-baroque stylings, marvelous Villeroy & Boch floor tiles, and a shaded rear garden, was built by a German architect, Carl Zaar, in 1903-05 for the entrepreneur and philanthropist David Sarajishvili, who made his fortune with high-quality cognac. After his death, it was sold to another industrialist, Akaki Khoshtaria, who placed the house at Wardrop’s disposal.

Wardrop works tirelessly to secure Allied recognition of the new Georgian Republic. De facto recognition is granted in January 1920, though Wardrop does not celebrate for long. Ill health induces him to request replacement, and in April 1920; he leaves the country to recuperate in a sanatorium.

The dining room of Wardrop's residence, 2025.

“The Georgians, the original inhabitants of the Caucasus, are of very ancient stock. They are a brave and handsome race, as may be seen from the splendid type in the picture. This is the native dress, with the biretta and bandolier, the latter nowadays a mere picturesque adjunct, but formerly used for powder-flasks or cartridges.”

– Frederick George Aflalo, “An Idler in the Near East”, 1910.