Sites of Memory, 2025

Photography, print, exhibitions

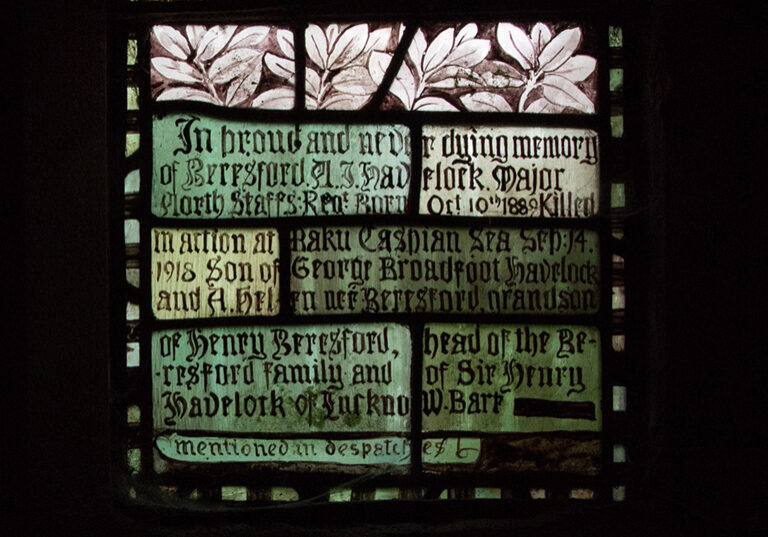

This project traces the journeys of young soldiers from my native Black Country region who served in the Caucasus in 1918-20 alongside Indian troops. The project was inspired by a discovery that some of the young British soldiers buried in Batumi, Tbilisi and Baku were born in my home region. Shedding new light on the period of the brief union between the British Empire and the Republic of Georgia, exhibitions using both contemporary photographs and archive materials from both UK and Georgian archives were presented in Sandwell and Tbilisi. These were complemented by a publication and online materials.

Our perception of the Great War is focused on those terrible battlefields of Flanders and France, but the conflict ranged far and wide, with Imperial forces in Africa, Italy, Russia, the Balkans, Palestine and Syria, the Dardanelles, Mesopotamia and Persia, as well as the Caucasus, places often called ‘the forgotten fronts.’

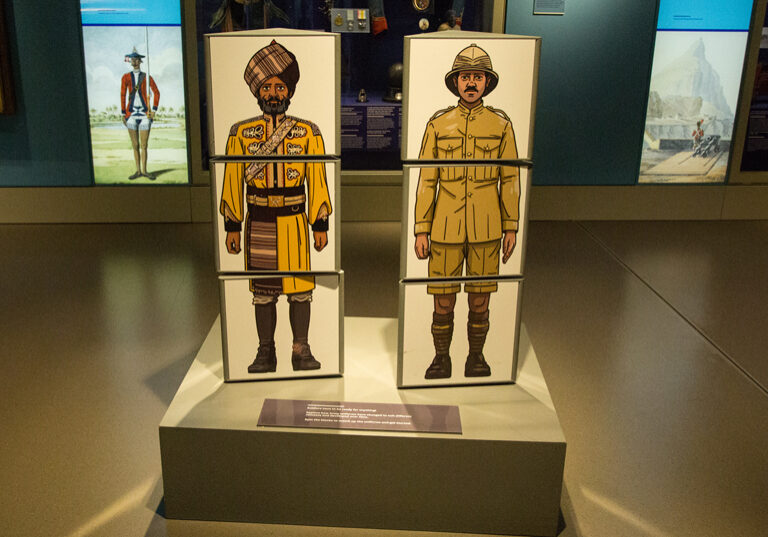

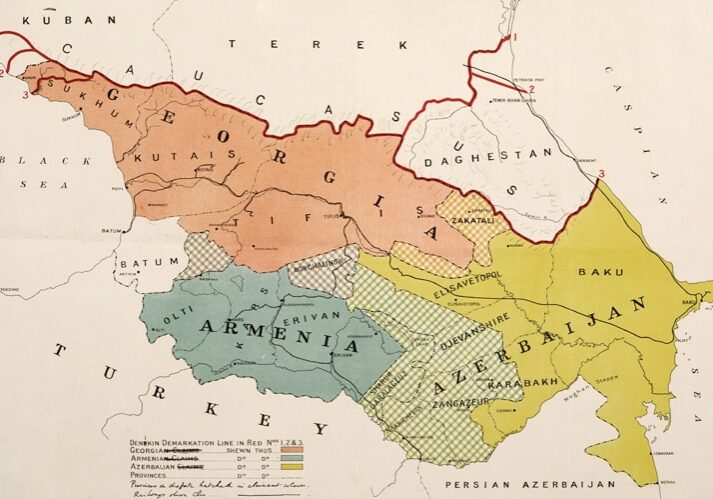

Some 12,000 British troops and 18,000 Indian troops were spread out along the Trans-Caucasian railway line between the oil refineries of Baku on the Caspian Sea and the port of Batumi on the Black Sea. Converging on the Caucasus in the west from the Salonika front, and in the east from Mesopotamia and Persia, they could be found in Poti, Tbilisi, Gagra, Shusha, Yerevan, Kars, Baku, Krasnovosk, and Petrovsk. At that time, there were Bolshevik armies in the north and east fighting the White armies of General Denikin in the north-west, along with armed peasant groups called the Green Guards who fought all factions, rebellious tribal groups in North Persia, a resurgent Turkish army under Ataturk to the south-west, and clashes between troops of the Georgian and Armenian states.

Eventually, the British government decides to withdraw from the region. With the commitment to demobilisation and troops needed to occupy parts of defeated Germany and Turkey, as well as growing troubles in Ireland, there are simply not enough resources. By July 1920, they had withdrawn to Batumi and then hand control of the port over to the Georgians, leaving behind only a small military mission in the country, which itself is evacuated as the Red Army invaded Georgia in March 1921.

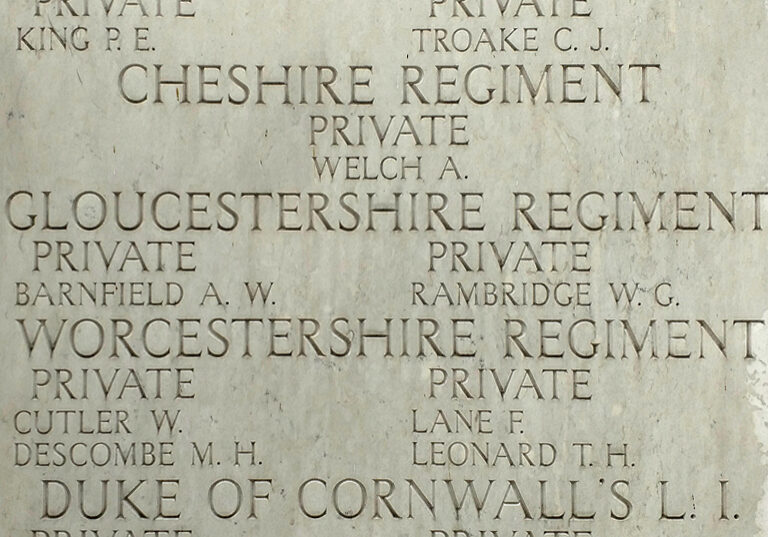

British military cemeteries left in the Caucasus were forgotten during Soviet times. In 2014, a memorial wall was finally erected in Batumi by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission near the believed site of the graves in hills above the port. In Tbilisi, a memorial stone installed in 2000 marks another site today, which can be found in the back garden of a private house, the area having been built over in the 1950s. In 1997, a memorial was designed for Baku, but permission to erect it was not forthcoming for several more years.

“The World War of 1914-18 was the greatest moral, spiritual and physical catastrophe in the entire history of the English people – a catastrophe whose consequences, all wholly evil, are still with us.” – Paul Johnson, historian.

As for the soldiers laid to their final rest here, before the war they worked as a dairyman, machine hand printer, a clerk, an architect, a plasterer, a gardener, a cab driver, a collier, a carter, labourer, apprentice cabinet maker, grocery shop boy, a solicitor, printer’s assistant, a farm worker, sanitary mould maker, a fitter and turner, a baker, a brickyard drawer, a shop boy for an optician, bricklayer, a wire boy, a coalman, a cotton reacher, a doctor’s groom, a joiner, a wharf assistant, a brass polisher, housepainter, a jeweller’s errand boy, a stoker, to name a few of their occupations before military service. Also buried here are men from Rajasthan, the Punjab, Nepal, China and Greece, all serving with the British.

Exhibitions were on view at Haden Hill House Museum, Cradley Heath, September-December 2025, and at Tbilisi Photography and Multimedia Museum in February 2026.

A bespoke limited edition publication – ‘Black Country, Black Sea’ – supplements the exhibition materials.

Thanks to: Sandwell Archives, The Royal Warwickshire Regiment 1914 - 1918 Living History Group, Georgian National Archives, TPMM, British Embassy Georgia.

And biggest thanks to Magda Nowakowska, who makes so many things possible.

Supported by the Arts Council of England