Image: Batumi port, 2025.

In western Georgia, Batumi lies on the shores of the Black Sea. With a current population of over 120,000, as a popular tourist destination I think of it as a cross between Blackpool and Las Vegas.

At the time of The Great War it was called Batoum. The poet Osip Mandelstam called it ‘a Russian-style California Goldrush city’ – for here was the terminus for the Trans-Caucasian railway, all 563 miles of it, bringing oil from the Caspian to be processed and shipped off. Adjacent the rails, a pipeline brings kerosene from Baku – before the war it pumped 980,000 tons of the stuff per annum. Here the Rothschilds and Nobels did business. Three hundred or so ships, full of kerosene and oil, left the port each year, a great deal of it required by the Royal Navy.

By the turn of the 20th century, apart from the UK, Turkey, Greece, Italy, Japan and Persia all had consulates here, with the United States, Belgium, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden and Norway having their official representatives in the port. There were 24 shipping companies with offices, with manganese, wool, cotton, maize, liquorice, tobacco, wine, wood, silk being exported. A Chinese merchant had established tea plantations inland, worked by Greek labour, mostly women. The British thought the hills above the own looked Nepalese, with orange and tangerine trees, palms and eucalyptus.

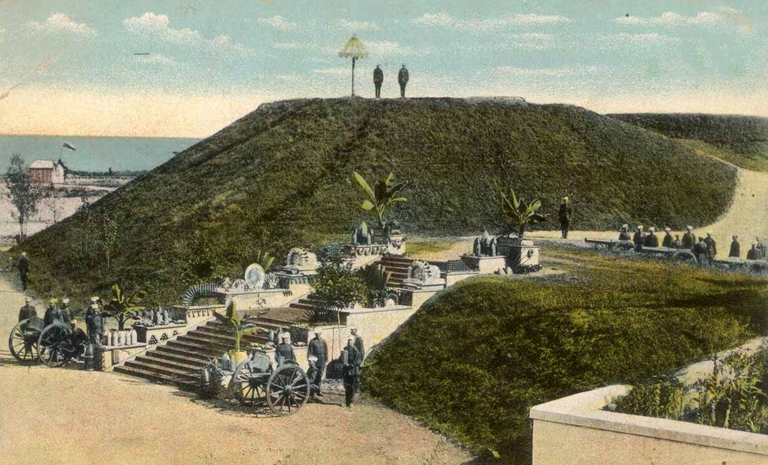

Postcard of Russian fort at Batumi, circa 1900. These kinds of postcards were made by a Swedish publishing house, Granberg Joint Stock Company in Stockholm, who produced thousands of such scenes for the Russian market at the beginning of the century up until the Revolution.

Of the British occupation, Victor Ilyitch Seroff, born in the town in 1902, wrote:

“The large number of British dreadnaughts and destroyers in the harbour of Batoum made that city the safest refuge for Russian émigrés of all classes. They flocked to Batoum in great numbers, and included the grocer who had abandoned his shop and the Tsar's ex-mistress. They brought with them all the characteristics of their former life, clubs, prostitutes, gambling houses, cabarets and dance halls. On every corner there were money exchange offices, and our own currency fell continually in value. Impressive bandits who had been operating extensively in Russia stopped on their way to Europe. They walked about town with their henchmen and bodyguards. They wore enormous fur hats and carried revolvers hanging from their belts. Secretaries paid their bills for them from large, fat wallets. Young, handsome girls became stenographers with the British forces. The boulevards, park and beach were filled with elegance such as we had never seen before in Batoum. The English brass band gave concerts every Sunday, and crowds of people stood listening to their well-executed pieces.”

British and Indian troops remained in Batumi until July 1920, when they handed over the port to the Georgian government.

Royal Marines parading at Batumi, 1919-20, Georgian National Archives.