Image: Paradise Street, along which now runs the Metro, 2025.

A few hundred yards from the classical Roman façade of Birmingham town hall on Paradise Street, you would once find an army recruiting office at Carlton Chambers. At the beginning of 1919, they were looking for volunteers to re-enlist for the ‘Russian Relief Force’ – these were troops to be sent to both North and South Russia (which included the Caucasus). Volunteers were required for the Royal Field Artillery, Royal Engineers (Field, Signal and Postal), Infantry, Machine Gun Corps, Royal Army Service Corps, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, Royal Army Veterinary Corps, and Army Pay Corps.

Carlton Chambers did not survive the Luftwaffe bombing raids on the city of Birmingham during the Second World War. It was adjacent to Queen’s College Chambers, originally a medical school, of which only the Grade II listed facade remains, beneath which the Metro line runs today.

Armistice Day, Birmingham, 1918. Personal photograph: John L. Lyne, Imperial War Museum collection Q 63690.

In the photograph, to the right is the museum and art gallery and to the left is the Chamberlain Memorial. Where the photographer is standing, over his left shoulder stands the town hall. On this day a crowd of over 100,000 people gathered in the city centre with bands playing and people dancing long into the evening.

Some months later, while there were volunteers ready to go to Russia, most of those already serving in the newly formed Army of the Black Sea fully expected to be demobilised and sent home. On 3 January 1919, the Birmingham Gazette published this letter:

THE WAR ON RUSSIA

(TO THE EDITOR OF THE BIRMINGHAM GAZETTE)

Sir. – I wonder how much longer we have got to wait before we have our men folk at home. My husband joined up at the outbreak of war, drafted to Salonika, served three years and four months out there. He has had his first leave, and as soon as he landed back was drafted to Russia. Why not send the conscripts that went last and release those that went first?

– Yours, etc., –Tamworth. A SOLDIER’S WIFE.

On 3 March, 1919, in a House of Commons debate on the number of land forces Britain should keep and issues of demobilisation, Churchill stated: We are half way between peace and war. In response, James Hogge, an MP for Edinburgh commented: I thought we had given up war! Another shouted out, I thought this was a war to end war!

By way of explanation Churchill went on to say:

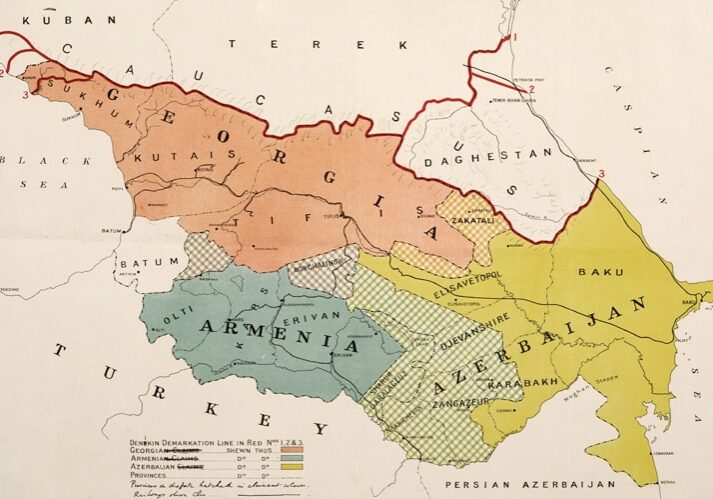

“At the other end of Russia, in the extreme South, we have an Army of a moderate size, but of a certain size, in the Caucasus. These troops were sent there when the Turkish resistance collapsed, and they were sent there for the purpose of making sure that the German and Turkish forces were turned out of the country. They remain there for the purpose of maintaining order in these wide regions and among these turbulent peoples, pending the decision of the Peace Conference as to their future. In consequence, we are now holding in some force the railway line from Batum to Baku, with our headquarters at Tiflis, and the Admiralty have a fleet of armed vessels on the Caspian which gives us the command of that extensive inland sea. In this theatre we have no special British interests of any sort to serve, nor are we under any special obligations to the inhabitants. We are simply discharging a duty to the League of Nations or to the League of Allied Nations, and endeavouring to prevent new areas of the world from degenerating into the welter of Bolshevik anarchy.”

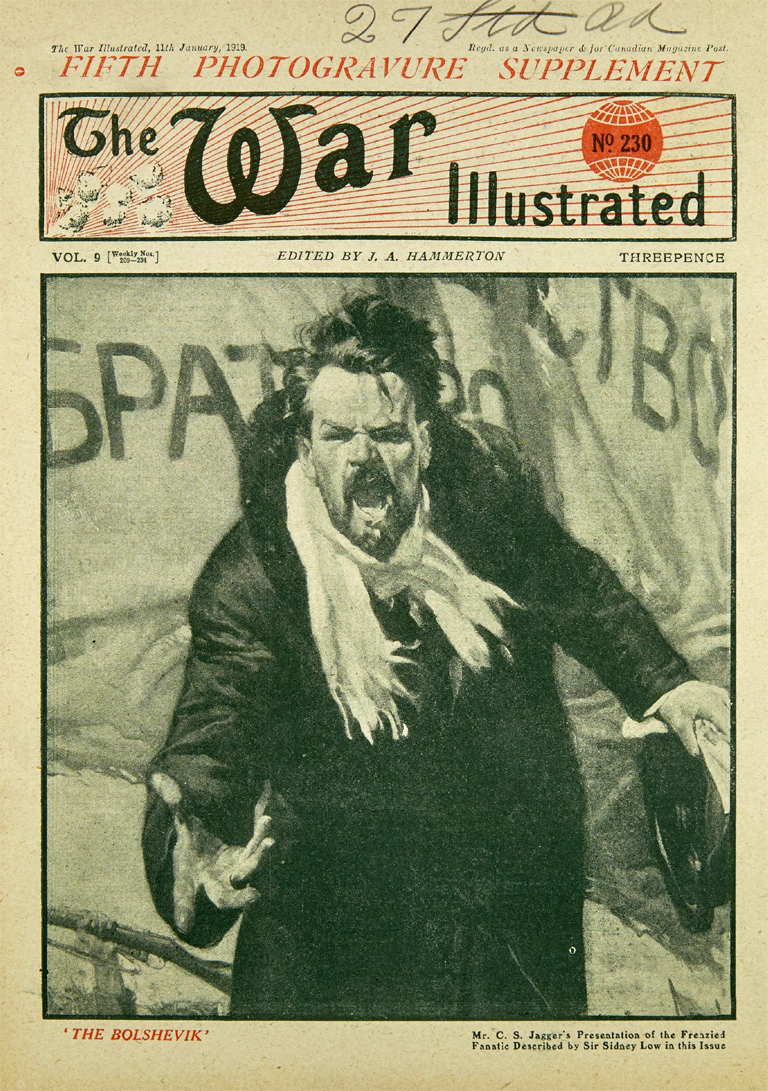

Cover of The War Illustrated, 11 January 1919. Published in London between August 1914 and February 1919, which featured maps, photographs and illustrations, the work of war artists, weekly reporting and editorials on the conduct, events, and consequences of the war.

Published in London between August 1914 and February 1919, The War Illustrated magazine featured maps, photographs and illustrations, the work of war artists, weekly reporting and editorials on the conduct, events, and consequences of the war. The cover illustrates an article: “Bolshevism in its True Colours.”

In this particular issue, Sir Sidney Lowe, journalist, historian, and essayist, writes: “I suppose that some of the apologists for Bolshevism would say that, in spite of the blood-bath and misery in which it has plunged Russia, there is something to be said for its underlying ideas. They think that it seeks to enthrone democracy. But there is nothing democratic in the Lenin-Trotsky Government. On the contrary it is essentially a tyranny, no whit less despotic than that of the Tsars; far more savage and brutal in its methods, and resting quite as little as any autocracy on popular consent. There is not a trace of true democracy in the rule of a small group of persons who have gained power by violence and are maintaining it by means of a corps of mercenary troops.”