Image: End of the line, Batumi, 2025. At the time of the British occupation of 1919-20, the rail line ran straight into the town, one line to the docks and one along the main street.

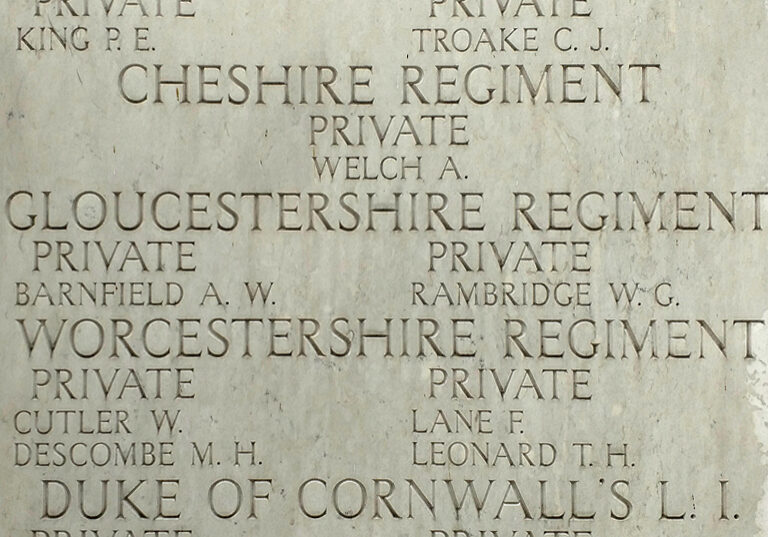

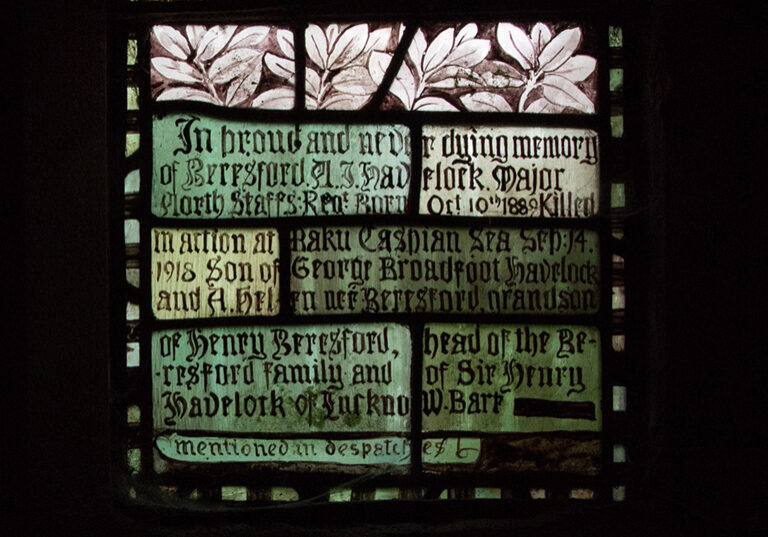

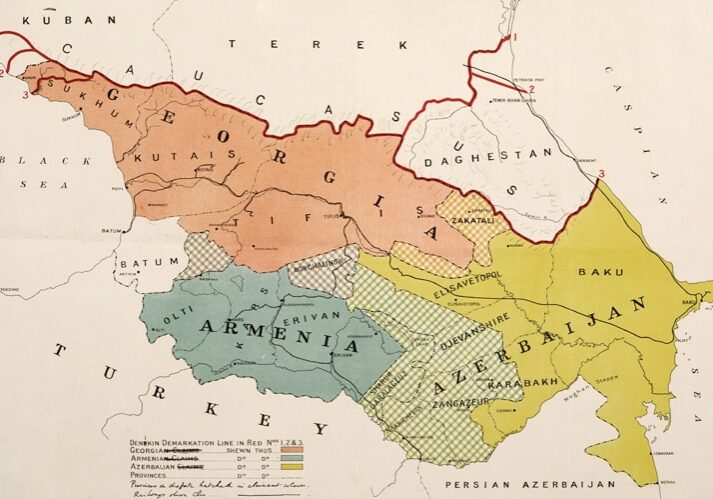

The expansion of Batumi began in 1883 with the final construction of the Batumi–Tiflis–Baku railway, built with the help of English and Polish engineers, which allowed for the transport of oil and kerosene in particular. Following the Armistice with Turkey by early 1919, some 12,000 British troops and 18,000 Indian troops were spread out along this railway line between the oil refineries of Baku on the Caspian Sea and the port of Batumi on the Black Sea.

Walter B. Harris, in his 1896 book ‘From Batum to Baghdad by way of Tiflis, Tabriz and Persian Kurdistan’ describes travelling on the railway:

“The railway stations are large and well built, and all appear to possess excellent refreshment-stalls, well supplied with food and drinks. But it is on the platform and not within that the centre of attraction for the traveller is to be found, in the strange groups of peasants and others who crowd down, either out of curiosity to see the train and its passengers, or else to sell their wares, for the stations become, for the few minutes that the trains remain, a centre of busy bargaining between the peasants and the passengers. Pigs, lambs, fowls, turkeys, and geese, and higher in the mountains chestnuts, apples, and bread, are all brought for sale, and a demure and well-dressed young officer in our compartment purchased for some small sum a couple of young sucking-pigs, which, safely stored in a sack, travelled with us to Tiflis under the seat.”

In December 1918, within days of the first British naval vessels docking in Batumi, an oil train arrived from Baku, the first in many years, escorted by a British Lieutenant and 20 soldiers from the 9th Worcesters.

In 2018, Michael Portillo makes the trip for his BBC series, Great Continental Railway Journeys. Armed with his 1913 Bradshaw’s Continental Railway Guide, he visits a tea plantation, enjoys wine, attends a supra of course, admires ancient frescoes, looks at mountain peaks, noting that a Briton was first to conquer the highest peak in the Caucasus range. (The higher western summit of Elbrus was first reached in 1874 by a British expedition led by F. Crauford Grove, known as a “gentleman traveller of independent means.” In the modern era “arriving in Tbilisi, Michael is struck by the warm welcome of Georgians.”

After relinquishing his wartime officer commission in April 1920, Oliver Baldwin travelled across the Caucasus and took up a job in Armenia as an infantry instructor, where he was imprisoned by Bolshevik-backed revolutionaries. In his memoir, from ‘Six prisons and two revolutions; adventures in Trans-Caucasia and Anatolia 1920-1921’. He wrote:

“A fairly uncomfortable night was passed in this compartment, which formerly had been a luxurious Russian Wagon-Lit, since the mattress, on which three of us crouched, had not been cleaned since the Revolution. The morning showed passing scenes of unparalleled beauty: the autumnal tints of rare trees flashed past showing a brilliant patchwork screen to our eyes. Great valleys, thickly wooded; open plains, dotted with hillocks on which ruined castles rested and sighed for their glory that had passed with Liberty's advent and the bitter warfare that the country had experienced in the reign of King Irakly the Second upon us. In the late afternoon we made the large curve that brings Tiflis into view, and there she lay glistening with fading sunshine on wet roofs and frowned on by her protecting cliff like Cape Town by Table Mountain after rain. The streets were wet and dark as I hurried to the station, and the heavy rolling clouds showed grey in the first pale rays of dawn. At the station, indescribable smells. Human forms asleep on the floor; baggage thickly piled; wet clothes sending fumes of musty dampness into every corner of the large booking-hall. Tartars, Georgians, Armenians; poor, starving, hopeless; moving, ever moving, unsettled by the past, harassed by the present, fearful of what was to come.”

En route to Tbilisi from Batumi, 2025.

Armored train with People’s Guard of Georgia, 1918-20. Georgian National Archives.

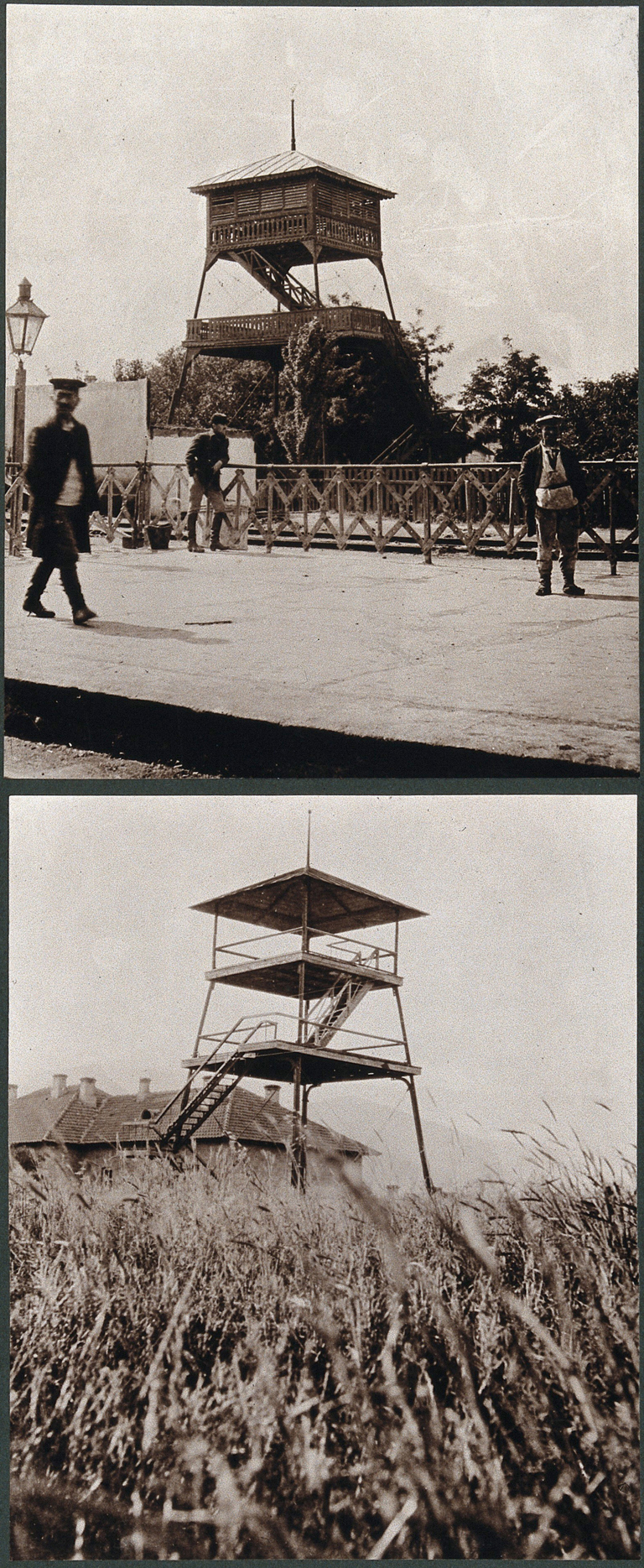

Malaria towers along the railway between Tiflis and Baku, circa 1900 -1920. Wellcome Collection reference: 564264i.

Malaria had been a constant and debilitating problem affecting the health of troops serving in Salonika and Mesopotamia. Malarial infections also occurred in Batoum, Petrovsk and elsewhere but, according to medical officers at the time, Baku and Tiflis remained comparatively free. One curiousity they may have encountered at stations along the railway between Tiflis and Baku were these construcions.

Natia Skhvitaridze, Assistant Professor, at the School of Health Sciences, UG, offers this explanation. ”As I remember, a ‘malaria tower’ refers to a type of elevated structure built several metres above the ground. These towers were designed to protect people from malaria, based on the belief — common in the 19th century — that the disease was caused by miasma rising from the ground. As we know now, despite the incorrectness of this assumption, it was widely accepted at the time. The idea was that by constructing temporary (wooden) shelters at higher elevations, especially during the rainy season, people could avoid exposure to the disease. Additionally, the elevated position provided natural ventilation, which in reality was really beneficial. These structures were particularly common in Italy and even in Iran, as I recall. However, I do not have any historical context regarding their use in Georgia.”