Image: Glass negative, circa 1919, showing a Royal Naval armoured ambulance breakdown in the Caucasus. This is one of a series of glass negatives collected by Surgeon Commander Montague Henry Knapp, Hon. Director of the Naval Medical Section of the Imperial War Museum and exhibited at Crystal Palace in June 1920.

The Wellcome Collection is a free museum and library near to Euston Station in London. It’s a treasure trove, a marvellous archive of medical history (along with a very nice cafe), but it also hosts art exhibitions relating to health. It opened in 2007, part of the Wellcome Trust, a charitable foundation originally established in 1936 with the aim of improving human health through research. As they state: “We believe everyone’s experience of health matters. Through our collections, exhibitions and events, in books and online, we explore the past, present and future of health.” The collection looks after many thousands of items relating to health, medicine and human experience, including rare books, artworks, films and videos, personal archives and objects.

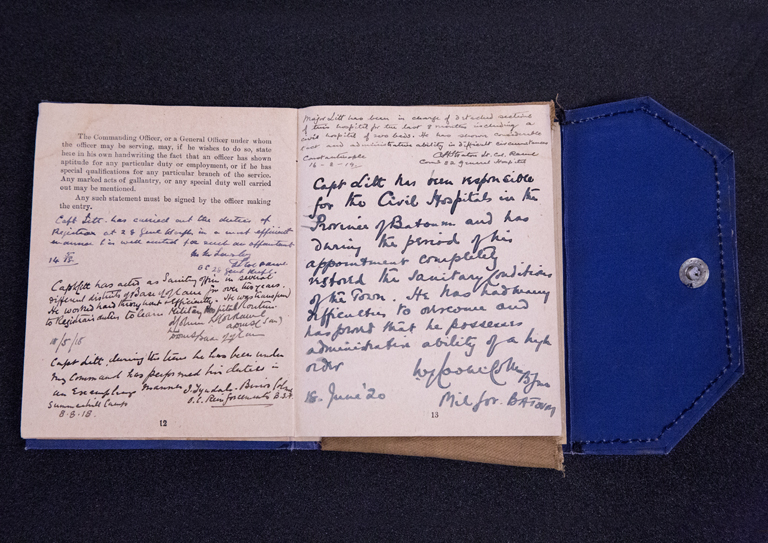

Diary of Captain John Percy Litt.

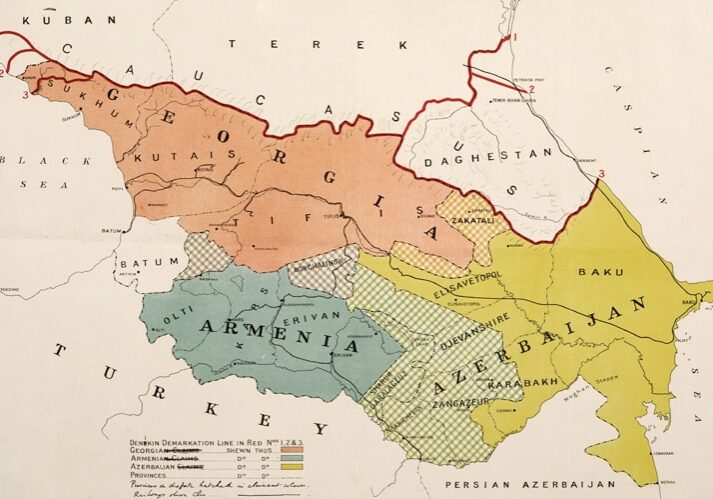

Among the manuscripts in their collection, there is a diary and a photograph album by Captain John Percy Litt, Royal Army Medical Corps (1887-1947). Litt joined the RAMC in September 1914, served in Salonika 1915-1918, then with the Army of he Black Sea 1918-1920, stationed in Batumi in 1920, and in Constantinople 1922-1923. He received the following commendation for General Cooke-Collis, Military Governor: “Capt Litt has been responsible for the Civic Hospitals in the Province of Batoum and has during the period of his appointment completely restored the sanitary conditions of the town. He has had many difficulties to overcome and has proved ha he possesses administrative ability of a high order.”

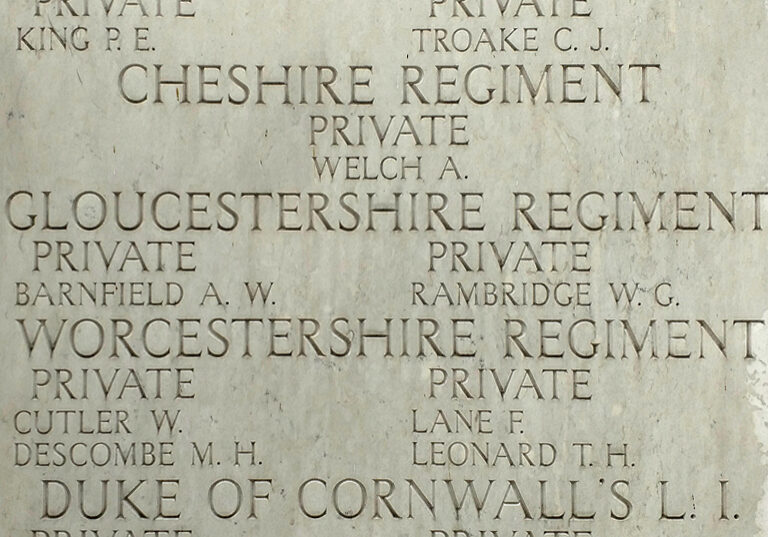

Almost opposite the Wellcome building, you will find the London and North Western Railway War Memorial, which commemorates their employees who were killed in the First World War. Some 37,000 LNWR employees left to fight, a third of the workforce, of whom over 3,000 were killed. It was unveiled in October 1921.

“Venereal diseases were the chief cause of inefficiency amongst the troops of the 27th Division. Malarial infections occurred in Batoum, Petrovsk and elsewhere, but Baku and Tiflis were comparatively free. Typhus fever, smallpox, dysentery and cholera were more or less prevalent amongst the civil population, but the troops were never seriously affected. Infectious jaundice was prevalent amongst the Indians of Malleson’s Force, and there were also a few cases of frostbite, but venereal disease was the most prevalent complaint amongst the British of this force also.

One of the field ambulances at Tiflis became a venereal disease hospital and the other a hospital for infectious diseases. No. 18 Stationary Hospital received the ordinary sick. At Baku No. 40 Combined Field Ambulance was set apart for infectious diseases. The Russian huts and hutted hospitals found at Batoum were well up to the standard of the British medical services, and were occupied by the British medical units. No. 21 Stationary Hospital at Batoum occupied the Russian Barracks, which had been converted into a hospital early in the war. It consisted of a number of pavilions, and all classes of surgical and medical cases, including infectious cases, could consequently be accommodated in it. No. 27 Casualty Clearing Station was in a hutted Russian hospital and received medical and surgical cases. The field ambulance was also in huts and became a venereal hospital. An Indian section, with an Indian establishment, was formed in all these units.

No. 28 Mobile Laboratory was established at No. 25 Casualty Clearing Station, Baku, and No. 27 Mobile Laboratory at No. 21 Stationary Hospital, Batoum. Dental centres were opened at Baku, Tiflis and Batoum.”

– Medical Services General History Vol IV, Royal Army Medical Corps, 1924, Major-General Sir W.G. Macpherson and Major T.J. Mitchell, D.S.O.